16D parody

Where to Look in the Law

Parody is governed by the statutes on derivative versions and on fair use. See the separate pages on those subjects within this web site.

What the Supreme Court Ruled

Jack Benny vs Loew’s Inc and Patrick Hamilton;

Columbia Broadcasting System and American Tobacco Company vs Loew’s Inc and Patrick Hamilton

S.D.Calif (5-6-1955) ¤ 131 F.Supp. 165, 105 USPQ 302

USCA 9th Cir (12-26-1956) ¤ 239 F.2d 532, 112 USPQ 11

U.S. Supreme Court aff’d (3-17-1958) ¤ 356 U.S. 43

Loew’s (the parent company of MGM) spent $2,458,000 to make the 1944 movie Gaslight, and the high quality and popular appeal of that movie was reflected in its substantial (for its era) gross rentals of $4,857,000 (reflecting the U.S. plus 56 foreign countries). The studio spent 2 ½ years to make it as good as it could be.

|

|

The District Court found (as summarized by the Court of Appeals) “The Jack Benny television play was copied in substantive part from Loew’s motion picture photoplay, ‘Gas Light’ [sic]; that the portion so copied was a substantive part of the copyrighted material in such photoplay; and that the Benny television presentation was an infringement of the copyrighted play…”

(Gaslight began as a theatrical play by Patrick Hamilton completed December 1938, published and copyrighted February 1939, then performed in England. A production in New York City premiered December 5, 1941, under the title Angel Street and ran 37 months. MGM bought the movie rights October 7, 1942.)

Benny, CBS, and sponsor American Tobacco said that their version was “fair use.” However, the District Court found “(1) That the locale and period of the works are the same; (2) the main setting is the same; (3) the characters are generally the same; (4) the story points are practically identical; (5) the development of the story, the treatment (except that defendants’ treatment is burlesque), the incidents, the sequence of events, the points of suspense, the climax are almost identical and finally (6) there has been a detailed borrowing of much of the dialogue with some variation in wording.”

The Appeals Court found: “If the material taken by [Benny, CBS and the sponsor] from ‘Gas Light’ is eliminated, there are left only a few gags, and some disconnected and incoherent dialogue.”

This Court devised an exaggeration indicating what would be permitted by precedent should “Auto Light” (the title of the Benny version) be judged not be an infringement: “The fact that a serious dramatic work is copied practically verbatim, and then presented with actors walking on their hands…, does not avoid infringement of the copyright… . Whether the audience is gripped with tense emotion in viewing the original drama, or … laughs at the burlesque, does not absolve the copier. Otherwise, any individual or corporation could appropriate, in its entirety, a serious and famous dramatic work, protected by copyright, merely by introducing comic devices … or facial distortions of the actors, and presenting it as burlesque. One person has the sole right to do this — the copyright owner, [in that] he has the exclusive right to make any other version”. (The Supreme Court affirmed the Appeals Court decision without issuing any comment of its own.)

illustration: Jack Benny in a photograph used in an ad which promoted his CBS series during the mid-1950s.

Luther R. Campbell, et al., vs Acuff-Rose Music, Inc.

510 U.S. 569 (3-7-1994) (This has become known as the “2 Live Crew” decision.)

Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., filed suit against petitioners, the members of the rap music group 2 Live Crew (among them, Luther R. Campbell, a.k.a. Luke Skywalker), and their record company, claiming that 2 Live Crew’s song Pretty Woman (1989) infringed Acuff-Rose’s copyright in Roy Orbison’s rock ballad Oh Pretty Woman (1964). The District Court held that 2 Live Crew’s song (written by Campbell) was a parody that made fair use of the original song. The Court of Appeals reversed, holding that the commercial nature of the parody rendered it presumptively unfair, that 2 Live Crew had taken too much of the original, and that market harm had been established by a presumption attaching to commercial uses. The Supreme Court reversed them, stating that fair use is established on “case-by-case analysis” and that “purposes such as criticism [or] comment” were met; and that parody is “fair use” where it is “transformative,” “altering the original with new expression, meaning, or message”, and “the copying [of lyrics] was not excessive in relation to the song’s parodic purpose”. (The Court admitted forming no opinion as to whether “repetition of the bass riff is excessive copying”.) In judging effect upon the market: “As to parody pure and simple, it is unlikely that the work will act as a substitute for the original, since the two works usually serve different market functions.”

The offering for sale of a recording of a copyrighted song is simple under U.S. copyright law: the manufacturer must pay “mechanicals” fees to the owners the song, the rates established by law. The licensing of a new performance entails permissions. A parody, for all its new material, nonetheless incorporates a performance of the original. 2 Live Crew had sought permission, but Acuff-Rose’s agent refused, stating that “I am aware of the success enjoyed by ‘The 2 Live Crews’, but I must inform you that we cannot permit the use of a parody of Oh, Pretty Woman.” 2 Live Crew did as they had planned: they put Pretty Woman on an album called As Clean As They Wanna Be. The authors of Pretty Woman were identified as Orbison and Dees and its publisher as Acuff-Rose.

“While we might not assign a high rank to the parodic element here, we think it fair to say that 2 Live Crew’s song reasonably could be perceived as commenting on the original or criticizing it, to some degree. 2 Live Crew juxtaposes the romantic musings of a man whose fantasy comes true with degrading taunts, a bawdy demand for sex, and a sigh of relief from paternal responsibility. The later words can be taken as a comment on the naivete of the original of an earlier day, as a rejection of its sentiment that ignores the ugliness of street life and the debasement that it signifies. It is this joinder of reference and ridicule that marks off the author’s choice of parody from the other types of comment and criticism that traditionally have had a claim to fair use protection as transformative works… .

“The fact that a parody may impair the market for derivative uses by the very effectiveness of its critical commentary is no more relevant under copyright than the like threat to the original market.”

What the Lower Courts Ruled

Columbia Pictures Corporation vs National Broadcasting Co.

USDC, S.D. Calif., Central Div. (12-9-1955) ¤ 137 F.Supp. 348, 107 USPQ 344

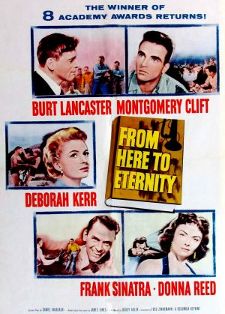

NBC broadcast on Sid Caesar’s prime-time network show a burlesque of From Here to Eternity called “From Here to Obscurity.” James Jones’s novel published February 26, 1951, was under copyright, as was the authorized movie adaptation released September 1, 1953. The Columbia movie would win eight Academy Award (including Best Picture), so the studio was angered that Caesar’s burlesque which aired September 12, 1953, was done “without the knowledge or consent of Columbia.”

|

|

Caesar’s version at 20 minutes could at most convey just a fraction of what the movie could at 100 minutes. Sid Caesar was cast as “Montgomery Bugle” and Imogene Coca as “Duchess”, a dancehall hostess. Neither character name corresponded to character names in Jones’s story, although actor Montgomery Clift had played a lead role. Likewise, “There is no substantial similarity between said burlesque and said motion picture as to theme, characterizations, general story line, detailed sequences of incidents, dialogue, points of suspense, sub-climax or climax.”

Allowances were to be made for Caesar’s version to evoke knowledge or memories of the original: “Since a burlesquer must make a sufficient use of the original to recall or conjure up the subject matter being burlesqued, the law permits more extensive use of the protectible portion of a copyright work… than in the creation or other fictional or dramatic works…, but not to the use of the general or entire story line and development of the original with its expression, points of suspense and build up to climax.”

The Judge did indicate that a line could be drawn past which parody would be infringement: “The defense, ‘I only burlesqued’ the copyrighted material is not per se a defense. To hold otherwise would seriously jeopardize right of property in copyrights and investments in such works, and would ultimately seriously damage the prices to be paid to authors for their literary works.”

The Judge who wrote this decision, James M. Carter, was the same District Judge who was first to rule against the more-extensive appropriation on trial in Benny v. Loew’s/CBS v. Loews and Loews v. CBS. (His rulings were affirmed by the Appeals Court and the Supreme Court; see summary above.)

Walt Disney Productions vs The Air Pirates, Hell Comics, et al

USCA 9th Cir. (9-5-1978) ¤ 581 F.2d 751, 199 USPQ 769

The defendants admitted “copying plaintiff Walt Disney Productions’ cartoon characters in defendants’ adult ‘counter-culture’ comic books.” The Court quotes one commentator who said that the defendants’ comic books “placed several well-known Disney cartoon characters incongruous settings” so that there would be “a rather bawdy depiction of the Disney characters as active members of a free thinking, promiscuous, drug-ingesting counterculture.”

The Court ruled: “The fair use defense cannot be applied to a copying which is virtually complete or almost verbatim.” Parodists might have “expressed their theme without copying the copyrighted cartoon characters almost verbatim,” but didn’t. “[W]hen the medium is a comic book, a recognizable caricature is not difficult to draw… . [T]he essence of this parody did not focus on how the characters looked, but rather parodied their personalities, their wholesomeness and their innocence. Thus arguably defendants’ copying could have been justified as necessary more easily if they had paralleled (with a few significant twists) Disney characters and their actions in a manner that conjured up the particular elements of the innocence of the characters that were to be satirized. While greater license may be necessary under those circumstances, here the copying of the graphic image appears to have no other purpose than to track Disney’s work as a whole as closely as possible.”

Cases Summarized in Other Sections |

| Hill vs Whalen & Martell (launch this) had the comic-strip characters Mutt & Jeff copied as Nutt & Geff in what was surely a blatant attempt to take some of the former’s audience. Warner Bros., Inc., Film Export, A.G., and DC Comics, Inc. vs American Broadcasting Companies, Inc., and Stephen J. Cannell Productions (launch this) had the rights-holders to Superman suing when a TV series copied familiar aspects of Superman as a means of highlighting the differences in the new show’s superhero character. |