When is a Particular Kind of Derivative Version Entitled to Copyright Protection as a Derivative Work?

The Copyright Office Weighed the Merits of Allowing Derivative-Work Copyrights on Colorized Versions of Movies

|

| |

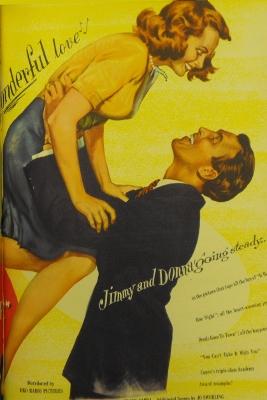

| When It’s a Wonderful Life was released to theaters in 1946, the distributor prepared two ads which began with two black-and-white photos obviously shot in the same session, and added colors that differed from one ad to the other. Obviously, one or both of the colored photos presented color choices that never matched the original objects. Four decades later, the United States Copyright Office was confronted with the question of whether or how to confer copyright status on colorized versions of whole movies. Some film historians and art purists decried colorization as a desecration of the original black and white film, but the Copyright Office decided that colorized versions were entitled to copyright registrations separate from the black and white version. It’s a Wonderful Life is an appropriate film to illustrate this issue with side-by-image images with different color schemes, because there were two different colorized versions of this film (one in 1986 from Hal Roach Studios, Inc., with work done by Colorization, Inc., the other in 1989 from Republic Pictures Corporation with work done by American Film Technologies, Inc. | ||

The concept of derivative works is the subject of an illustrations page of this web site. It is there that readers can learn more about the treatment under American law of compilations, adaptations, underlying works, abridgements, revisions, collections, and any other means by which an earlier work is incorporated into a subsequent one. (Links at the bottom of the page connect to seven pages of summaries of court decisions related to this topic.) Effort by itself does not make something eligible for copyright (courts have ruled this way) yet originality is enough for copyright to be conferred (here too, courts have ruled thus). When the Copyright Office began receiving requests to register works of a kind which never before had even been feasible, it had to decide whether to let there be registrations.

By the mid-1980s, companies sprang up which specialized in a new form of altering pre-existing copyrighted work: using computers for coloring entire movies originally shot in black-and-white. Colorization, Inc. sometimes contracted with the owners of older copyrighted films (most prominently Hal Roach Studios, Inc.) but often performed their modifications on movies that had fallen out of copyright (usually those that had been eligible for renewal but on which registration was not filed). Color Systems Technology had contracted with Turner Entertainment to add color to 150 movies in Turner’s massive library of films originally made by MGM, Warner Bros. and RKO. Both Colorization, Inc. and Color System Technology wanted the Copyright Office to accept registrations for colorized (or “computer-colored”) versions. Colorization, Inc. had spent $260,000 for just the conversion to color of It’s a Wonderful Life, on which it was relying that (a) the original black-and-white film was in the public domain for lack of renewal, and (b) its own work would be protected from infringement by means of a copyright on their derivative version. Although Colorization, Inc. had already shipped 125,000 VHS and Betamax cassettes to video stores by October 1986, “and TV syndication sales for it are booming” (according to an October 1986 news article), it wouldn’t always be the case that early sales would enable expenditures to be recouped quickly. Were copyright protection to be denied, the colorized edition of a public-domain movie would be in competition with legally-made unauthorized knock-offs after a very short time window. Even purveyors of computer-colored still-copyrighted black-and-white films preferred a separate copyright, so that the presumably-more-appealing new version could earn rental payments even after the original became fair game to everyone. (information sources: Los Angeles Times, October 2 and October 17, 1986)

The Copyright Office had to make its decision, and its role as an arm of Congress meant that the decision had to comply with the legal precepts already established. In June 1987, the Copyright Office issued its decision in the pages of the Federal Register (volume 52, pages 23443-23446). Below are portions that delineate that decision and which indicate the facts and principles which influenced that decision.

SUMMARY: This notice of a registration decision is issued to inform the public that the Copyright Office of the Library of Congress has determined that claims to copyright in certain computer-colorized versions of black and white motion pictures may be registered. The notice gives guidance to the public about the standards and practices governing registration of computer-colorized motion pictures. The notice also confirms the validity of existisig regulation 37 CFR 201.1(a), prohibiting copyright registration for mere variations of coloring. * * * The Copyright Act also spells out that copyright protection in a derivative work “extends only to the material contributed by the author of such work, as distinguished from the preexisting material employed in the work, and does not imply any exclusive right in the preexisting material. The copyright in such work is independent, of, and does not affect or enlarge the scope, duration, ownership, or subsistence of, any copyright protection in the preexisting material.” 17 U.S.C. 103(b) (emphasis added). * * * … Courts have held that while color per se is uncopyrightable and unregistrable, arrangements or combinations of colors may warrant copyright protection.1 * * * … the Copyright Office specified that aesthetic or moral arguments about the propriety of coloring black and white film did not, and could not, form any part of its inquiry.2 2. Summary of the Comments In all 46 comments (43 original and three reply) were filed with the Copyright Office. Despite the Copyright Office’s caveat against arguments regarding aesthetic considerations, many of the comments filed related simply to the question of whether or not the commentator found the colorized motion picture aesthetically pleasing. And most did not. * * * (b) Representing a modicum of creativity. * * * 4. Registration Decision After studying the comments responsive to the questions listed above, the Copyright Act, and the case law, the Copyright Office has concluded that certain colorized versions of black and white motion pictures are eligible for copyright registration as derivative works. The Office will register as derivative works those color versions that reveal a certain minimum amount of individual creative human authorship. This decision is restricted to the colorized films prepared through the computer-colorization process described above. * * * 1. See also 1 Nimmer on Copyright 3 § 2.14 (1985). Dated: June 11, 1987. |

Readers may profit from studying the arguments so as to understand which aspects of the adding of color to pre-existing movies were specifically relevant to the decision to grant copyright copyright status to them—and which ones were not considered in and of themselves to not warrant protection. In the event of yet another new twist on an old medium, these types of arguments might come under scrutiny again. Those wanting to read the full text of the above Federal Register announcement should seek from a reputable source (online or from a librarian) the text matching citation 52 FR 23443-23446.

Incidentally, computer-colored movies and television programs proved after a time not to draw substantially larger new audiences to older entertainment. The use of the practice came to be confined to a small number of specialized or enduringly-popular titles. Rob Word of Hal Roach Studios stated at a 1987 Senate Hearing, “We would not be doing this if we did not feel that we could at least get our money back through colorizing the film. But besides that, we are taking a film that nobody really cared about, preserving it, giving it lasting value and making it available to the public in both black and white and color.” (Reported in 53 FR 29889) It didn’t work out that way.

The Copyright Registration and Renewal Information Chart and Web Site

© 2007-2011 David P. Hayes